Open Door Policy, or How I've Let Myself In

“The fear […] was of being overwhelmed, of disintegrating under a pressure of reality greater than a mind, accustomed to living […] in a cosy world of symbols, could possibly bear."

— Aldous Huxley, ‘The Doors of Perception’

If you’ve read anything related to information security in the past, chances are you’ve come across the following term:

Attack Surface Reduction

It’s one of the first suggestions that gets thrown around for securing software. And it makes sense: You cannot attack something that’s not there1!

Reducing the surface could be done by simply removing every input from an application, but that would render it quite useless. Having a couple of choke points that can be audited thoroughly is the next best thing.

Actually mapping the attack surface is also context-dependent. We previously discovered a post-authentication vulnerability that allowed for remote code execution. Because exploitation required a valid user account, the vendor may or may not choose to include the vulnerable endpoint into their attack surface.

This endpoint let us execute code like it’s straight out of a Capture the Flag event2, so we were gently eased into the concepts involved in exploiting a remote system end-to-end.

Additionally, our privilege escalation vector relied on misconfiguration. While this is a very frequent occurrence, it still didn’t feel quite right.

Like Ned Williamson stated in one of his talks: We grow by tackling something that’s barely achievable. So while our previous adventures were a perfect fit for my former skill level, it’s time to end this specific research journey on a high ♫:

How about we dramatically reduce the attack surface ourselves by only working with unauthenticated requests? That would certainly make for a nice challenge. Let’s handicap us even further by only allowing the usage of components that are packaged into a default installation of said software. A self-sufficient exploit chain, unconcerned about the current patch level of the machine. I like it.

In this article, we’re going from discovering and exploiting another initial remote code execution vector to escalating our privileges by abusing a powerful internal service.

By the end, we’ll have taken over the machine remotely within a single HTTP request.

Disclaimer

It took a while and the very severe issues presented in this article, but the vendor has finally taken some actions. We had a couple of meetings and received status updates and I even got to talk to the developers directly. That’s a lot less draining than going through management every time.

All in all, they were thankful for the findings and are actively working on fixing them. Some things are already fixed, while others are supposedly more challenging.

It seems like their management wants to be quiet about those security issues, which is the wrong thing to do in my opinion. I’m not Project Zero, though, so I won’t go rogue and release every detail just yet. That’s why everything vendor specific remains censored.

So while it’s still not time to polish my CV with some CVEs, at least the vulnerabilities are being worked on.

No more gatekeeping!

How do we get an initial foothold into the server without the luxury of our friendly endpoint?

In the presence of a file upload vulnerability, we could upload a web shell and execute commands or code that way. Maybe we find a XXE injection vulnerability, which in very rare cases3 can lead to code execution.

However, our target server is written in C# and every uploaded file resides in a safe location outside the server’s root directory, so no dice!

There’s a third, very popular attack vector for executing custom code: Insecure Deserialization.

In order to understand the issue, let’s quickly define what serialization even means:

Serilization is the process of transforming data structures or objects with internal state into a format that can be stored or transmitted easily.

Or for you diagram loving people:

An object with internal state gets serialized into some common format and…

HOLD ON!

That serialized object becomes the input of some deserializing function down the line. Any input is bad news, as every self-respecting and more importantly self-proclaimed information security specialist knows.

But what can actually go wrong?

Exploiting Insecure Deserialization

I don’t remember if I heard about this vector while binge watching security conference talks, or if it came up during my own research into RCE in web applications. In any case, there’s one talk that had a huge impact: Attacking .NET deserialization by Alvaro Muñoz.

The talk does an exceptional job of explaining the details, so I’m not even going to bother.

Moreover, the author also released the YSoSerial.Net tool that can generate a multitude of different payloads depending on the target. What’s a target? There are numerous classes that can handle the deserialization, so every one of those might be a different target.

Deserialization exploitation also has the concepts of gadgets4, which are types with methods that get invoked during the deserialization process. Those invocations can lead to malicious behavior when controlled correctly.

Some gadgets may or may not be available to our application, depending on the environment. Combining multiple gadgets into a whole chain can result into custom code execution.

This seems rather brittle, but two things are important here:

- The actual payload can be generated with

YSoSerial.Net. - We know what formatters to look for (

LosFormatter,SoapFormatter,BinaryFormatter…)

Armed with this knowledge, let’s go find us some vulnerable formatter!

Hunting the Illusive Formatter

Knowing what kind of formatters to look for, the analysis becomes almost trivial with the program at hand. Now it’s only a matter of decompiling it and its libraries with our favorite .NET decompiler and looking through the results.

I’ve came across the infamous BinaryFormatter pretty quickly. Microsoft has a dedicated site that explains deserialization risks in general. The BinaryFormatter spearheads that list, that’s how infamous it is!

The documentation states:

The BinaryFormatter type is dangerous and is not recommended for data processing. Applications should stop using BinaryFormatter as soon as possible, even if they believe the data they’re processing to be trustworthy. BinaryFormatter is insecure and can’t be made secure.

One person’s security nightmare is the other person’s dream come true!

Now that we’ve verified the existence of the BinaryFormatter in the program, the much more important question becomes:

Can we actually reach it with an unauthenticated request?

That part took way longer than expected. For starters, the code base is enormous. Interfaces upon interfaces, the most indirect indirection imaginable. I wouldn’t make my arch-nemesis draw a fucking UML diagram of that mess5!

Tracing the input backwards from the BinaryFormatter is virtually impossible, because all those indirections kill the decompiler’s “Used By” function.

Fed up with the bullshit, I’ve decided to switch things up by dynamically analyzing the program.

No matter how many times I’m attaching a debugger to a running process, I’m always fascinated. Hopefully that feeling never goes away!

So here we are, repeatedly making requests to various known endpoints while simultaneously trying to set break points earlier and earlier into the request handling code.

After what seems like a lifetime, I noticed other code paths that reference this endpoint:

/native/<redacted>/anonymous/

Looking at it, this endpoint seems highly suspicious 🥸. Naturally, it’s not mentioned anywhere.

An Emotional 🎢

After being ecstatic about the finding, doubts started to creep in:

They use their own wrapper class around the BinaryFormatter. Maybe they do some sanitization in there? How do I even deliver the payload?

I’ll spare you most of the tedious details, but it took quite a lot of experimenting. There were so many moving parts that I had trouble to isolate the problems. A few highlights:

Choosing the right gadget chain. How do I even know which gadgets are “in the class path”?

Letting YSoSerial.Net generate a Base64 encoded payload, because the raw binary one didn’t work. Afterwards I’ve had to use CyberChef to decode that payload and save it to a file. Why the intermediary step? Because computers!

How do I put the binary file into the body of the request so that it doesn’t get messed with?

I tested some steps in demo programs and at some point even hot-patched the running application with the help of dnSpy. All in all a pretty amazing way for learning new techniques, but also quite tiring.

The icing on the 🎂, however, was my calc popping proof of concept. As is tradition for exploits, starting the calculator app is proof of code execution on a machine.

Not a single fucking calculator popped!

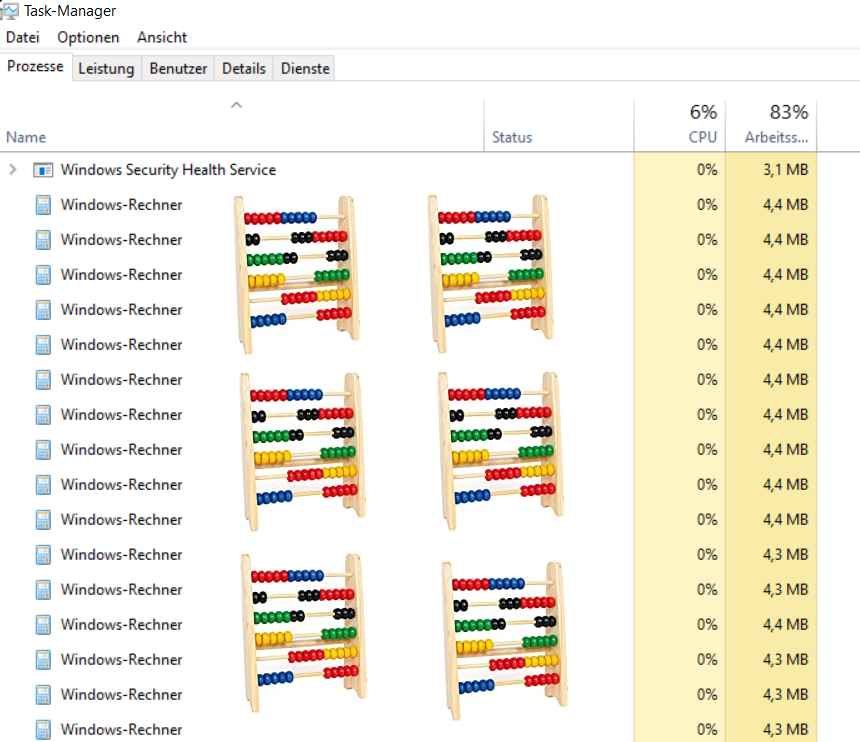

Right at the brink of insanity, I checked within the Task-Manager and saw dozens of calc.exe processes:

Figure 1: Traditional proof of exploitability

In hindsight it’s obvious: Inside the VM, I was logged in as admin. The IIS Appool\<appname> user that executes our code, however, doesn’t have access to my desktop. So while the process does get started, it doesn’t show up on my desktop.

Allow me to share my notes from the time to highlight just how happy I was:

I think it works. I actually think it works! [It] fucking does show it pops! YEEE[…]EEEAH!

I can still feel the rush!

Here’s the final command for generating the calculator payload. Except for the gadget, it was taken straight from the example section in YSoSerial.Net's readme.

$ ./ysoserial.exe -f BinaryFormatter -g WindowsIdentity -o base64 -c "calc" -t

Most of the YSoSerial gadgets let you specify a command like that. But how do we actually run custom code?

Honestly, it took me a while to find out. But reading the output of --fullhelp carefully, we can see this:

| |

Line 6 mentions the ExploitClass, which is part of the repository. The constructor of that class is the place where we write our code. After building the project and executing the following command, we receive our custom code payload.

$ ./ysoserial.exe -f BinaryFormatter -g ActivitySurrogateSelector -c -o base64

Even though the command parameter is ignored, the -c flag must be specified!

Finally, let’s send our payload to the server in a way that doesn’t mess with the bits and bytes:

$ curl -X POST --data-binary "@./OpenDoorPolicy-PoC.bin" http://<hostname>/<redacted>/<redacted>/<redacted>/native/<redacted>/anonymous/ --output - -v

Oh my, that was a lot of work to get another initial attack mounted. We’re not even half done here, though:

Our code only runs in the context of the IIS Apppool\<appname> user. We need some way to further escalate privileges. So what exactly do we put into the payload? Wanting to stay inside the vendor’s ecosystem, what options do we have available?

Fileserver

Introducing the Fileserver (FS), which is responsible for handling… exactly.

It’s the only Windows service left that runs by default in the newest version of the product. Oh, it also runs as LocalSystem, which makes it a perfect target.

Why they need an extra service to handle files is beyond me. There’s also some caching going on with multiple of those services distributed across machines, but it’s not the default setup. Probably it’s just a legacy thing for the GUI app in order to directly talk to it.

Actually I’ve already talked about it in the first article of this series. We exploited this very service by planting two DLLs next to it with a technique called DLL Proxying.

This time, however, the FS binary is located in a restricted location (C:\Program Files (x86)\), which is actually the default path. We cannot access it with our IIS Appool user.

Consequently, we are not able to simply drop our DLLs from within the deserialization code that gets run in the context of said user.

If only there was a service that allowed us to write files to arbitrary locations…

HOLD ON!

Maybe we can use the FS itself to do the deed?

At this point, I’ve had many questions:

- How does communication with the

FSwork? - Is there some form of authentication?

- Am I a wizard?

Overanalyzing the Fileserver

Alright, let’s take this one step at a time. What are our options? We could throw the binary into a disassembler, capture and analyze any communication traffic or even attach a debugger to the running process.

Let’s start small, though, by simply running the binary manually inside a test VM. The help menu helpfully informs us about the presence of a debug mode, which instructs the program to print many interesting things to the console at runtime.

The first thing we see after starting is that the listening port is already taken. After shutting down the service instance of the binary, it works. We get informed that the program listens on port 7600.

Cool, but what does it listen for? HTTP requests?

This right here is not your sophisticated microservice class, so hold your containers! It’s simply listening for TCP connections in order to send and receive the raw bytes that constitute its custom protocol. How do I know, you ask? Well, let’s dive into dynamic analysis, specifically capturing and analyzing network traffic.

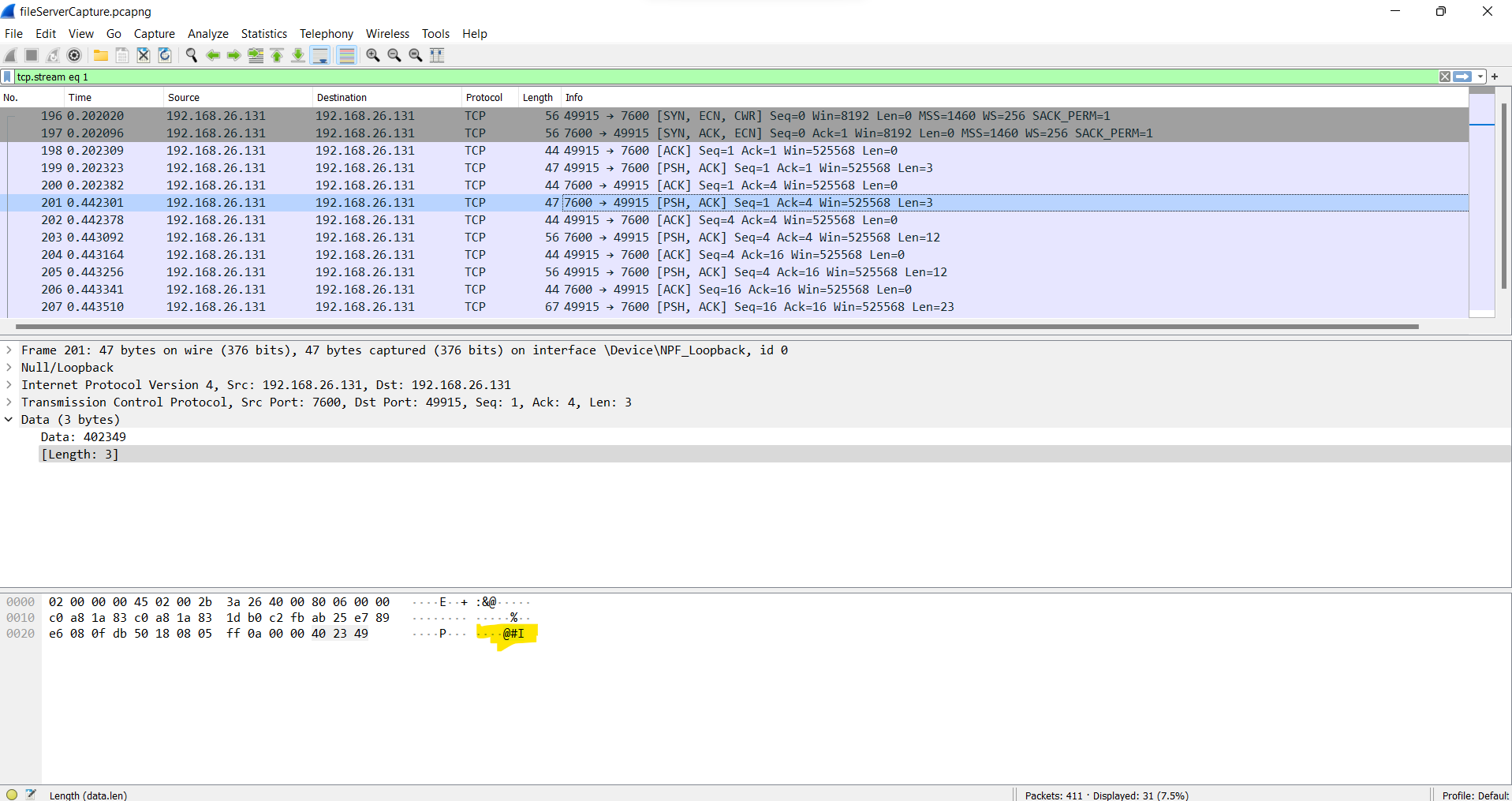

We start a capture session from within the wonderful WireShark and use the vendor’s GUI client to upload a file. We stop the capture immediately to reduce noise.

Did we catch something of interest? We know the destination port, so we could use it as a filter. But because there’s not much going on in my test VM, we simply take the first TCP stream:

Figure 2: Dirty Talk: “@#I”

I didn’t know at the time, but the @#I means “Let’s talk binary” and is part of the initial handshake.

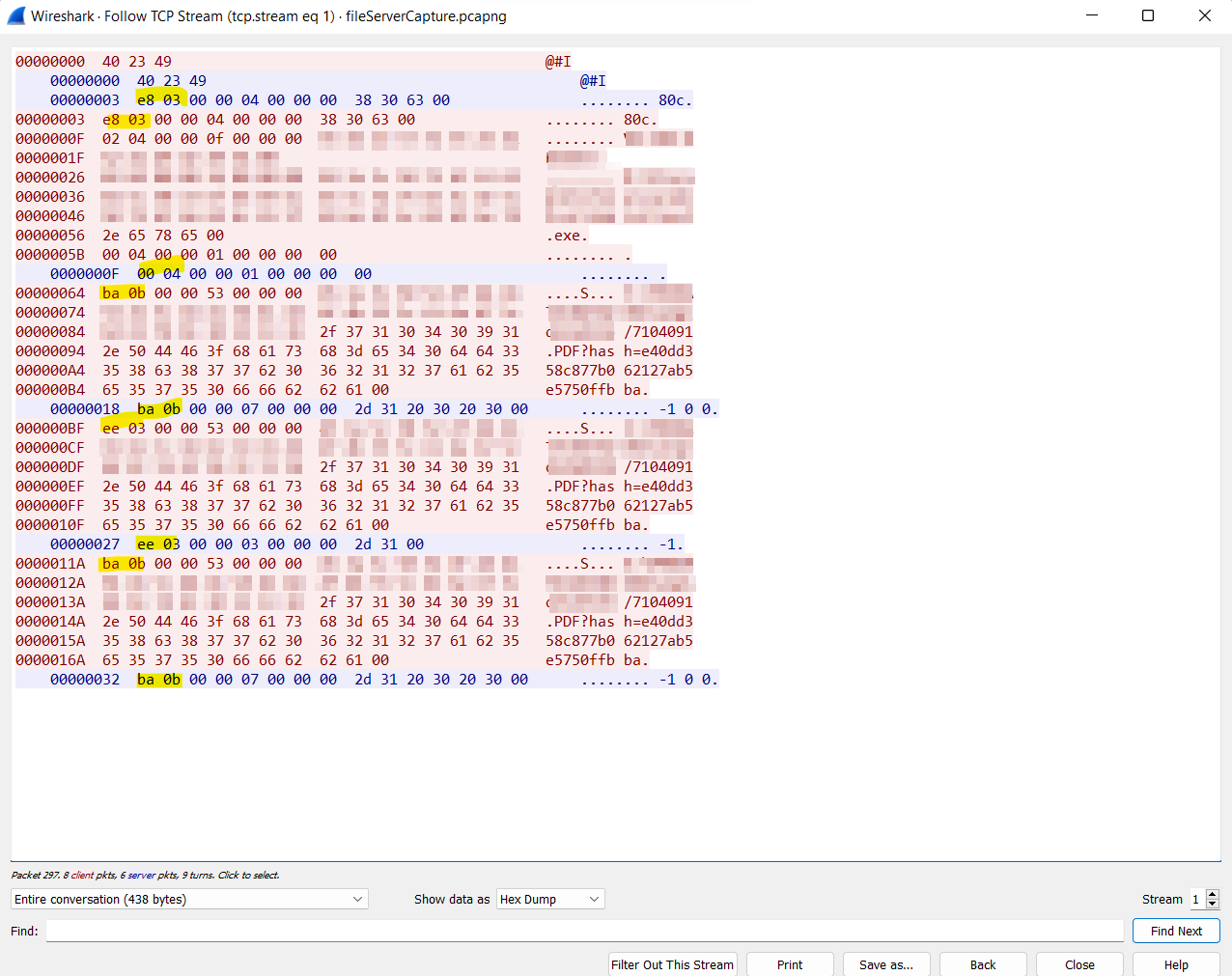

Even though there’s not much going on inside the VM, its still extremely useful to only focus on a specific conversation. We can achieve this by following the stream inside WireShark:

Figure 3: The whole stream of consciousness

The red lines are requests by the client and the blue lines are responses by the FS. I’ve marked some interesting byte patterns in yellow.

Even without reading Attacking Network Protocols, it’s a safe bet that the beginning of each request/response is some sort of command identifier. Take the first one for example, which is the little endian representation of 0x3e8. We’ll demystify it in a second.

If those bytes really are commands, we can probably find a giant switch statement inside the disassembled binary. Wait, do we even need to disassemble it?

Is it a .NET assembly written in C#? This would mean we can throw it in our favorite .NET decompiler and get a beautiful decompilation.

Or is it a native binary written in something like C/C++? In that case, we really need to disassemble it with our favorite disassembler.

Let’s find out:

| |

So disassembling it is!

I spent quite a few hours looking at the binary. I’m a bloody beginner when it comes to reversing, but it’s just so much fun. That whole binary reversing/exploitation topic still has such a strong allure, even though I’ve mainly been looking at higher-level web and .NET things in the past.

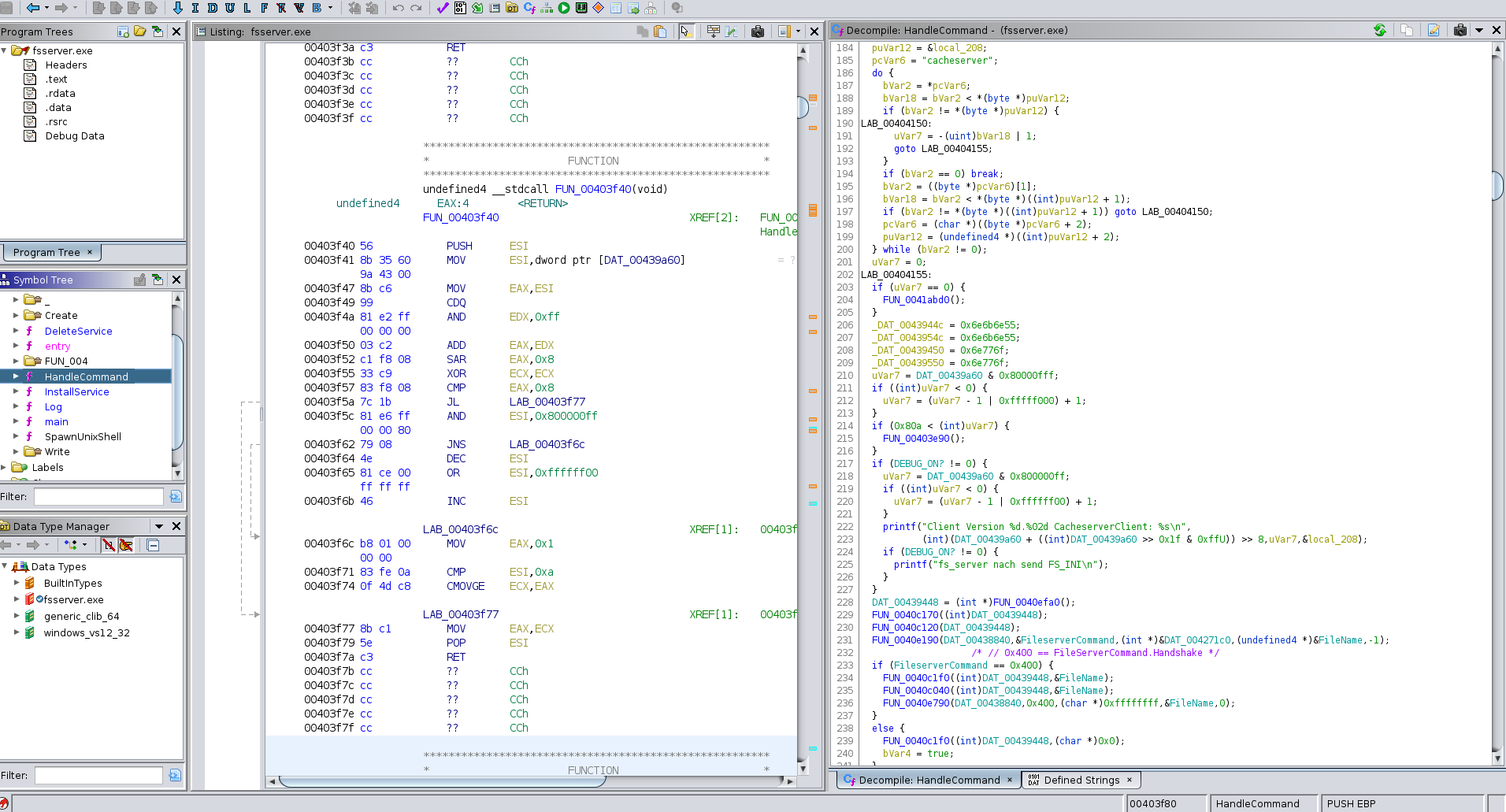

Anyway, the binary contains plenty of interesting strings, but no symbols. After looking around for a while, I found the HandleCommand function (named by myself):

Figure 4: The Fileserver binary in Ghidra

Look at that beautiful sight. There’s nothing more soothing than slowly reversing a binary…

HOLD ON!

While it’s nice to get to know the binary from different angles, what’s the actual endgame here?

Let’s weigh our options. We could check

- how every size argument for

memcpy()is calculated. - how user input flows into string formatting functions.

- how heap objects are managed (

heap overflow,double free)

With some elbow grease, we could even write a custom fuzzer that does some of that work for us.

I’m positive that we’d find plenty of things! But then what? There’s simply no way I’m going to be able to actually exploit those vulnerabilities on a modern system with my current abilities.

I’ve got sidetracked quite a bit by the aforementioned allure of binary exploitation, but remember:

“If only there was a service that allowed us to write files to arbitrary locations."

— Myself, ‘Open-Door Policy, or How I’ve Let Myself In’

Let’s be smart about this! We don’t need to exploit memory corruption. We only need to exploit the intended behavior of the service!

Can’t we simply issue commands to the FS and plant our malicious files that way?

Serving Files as God Intended

At first I wanted to write my own FS client based on the reversing work done previously. But again: Let’s be smart about this. The vendor must have a way of talking to it, too. Right?

Right! And I’ve stumbled over it before without paying too much attention: The Fileserver.Client DLL. It gets installed into the Global Assembly Cache (GAC) automatically by the vendor.

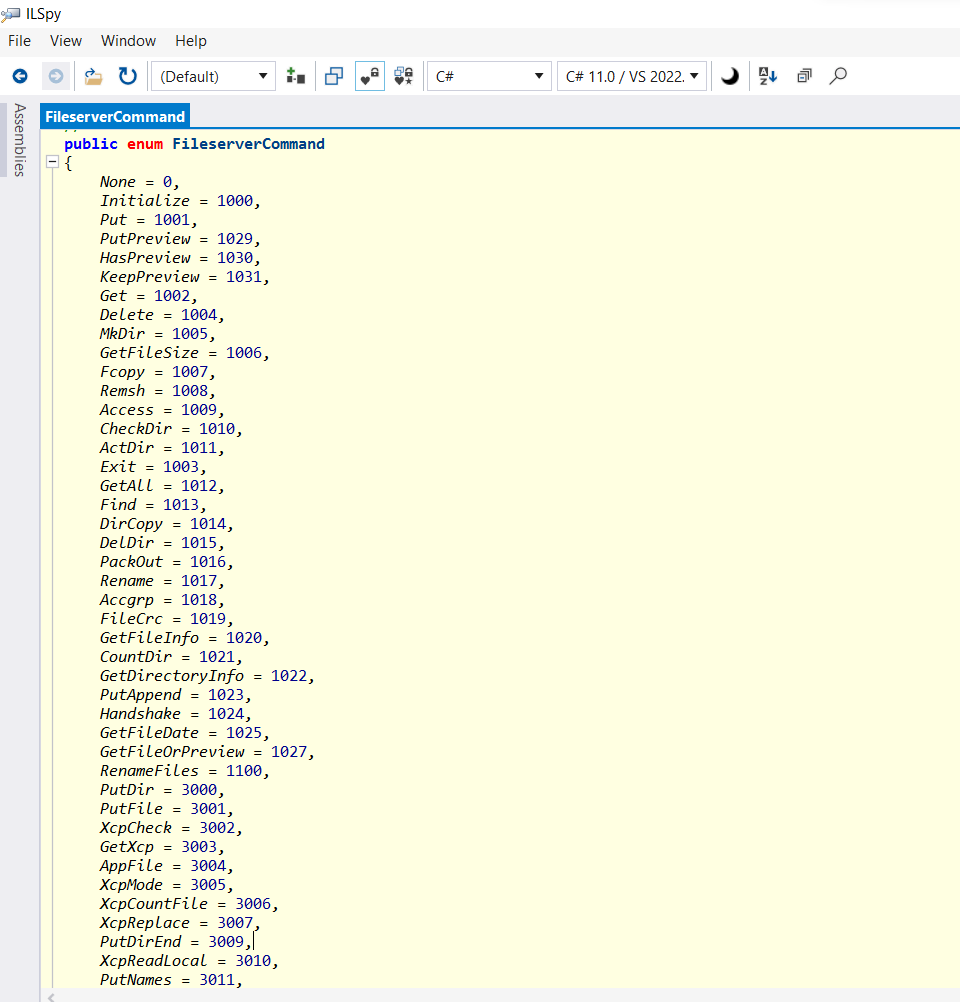

Finally it’s the .NET decompiler’s time to shine:

Figure 5: An excerpt of all the possible commands

Oh look, there’s our 0x3e8 from above, but decimal:

| |

decimal: 1000

Cool, so those bytes correspond to the Initialize command. Makes sense, right?

At this point we’re not really interested in the details any more, because the library provides us with much higher-level functions like Connect() and WriteFile().

We still don’t know if there’s an authentication mechanism in place, so let’s write a small demo program. We’re going to execute it directly on the server in order to eliminate all the uncertainties of the deserialization process.

After creating a .NET Framework console application and specifying the Fileserver.Client DLL as a dependency manually, our editor of choice is able to give us that IntelliSense goodness.

Writing the program is straightforward. But does it actually allow us to write files in forbidden places?

I’ll save us both the bandwidth by leaving out a screenshot showing a hilariously-named file in a folder, but it absolutely works! That’s a very important stepping stone on our way to glory.

There is, however, a problem. You see, we specified the DLL as a dependency in our project in order to get a hold of those nice types.

So what’s the problem?

Dependency management is complicated, not only in the .NET world. Our referenced DLL has a specific version. But another version of that DLL could be on the server, which might break our exploit. So in order to stay as generic as possible, we need another way of calling those functions.

Thankfully, we already used one of the nicest .NET features extensively: Our good old friend Reflection.

If our previous adventures taught us anything, it’s that the Reflection system is extremely useful in restricted environments. In the end, everything comes down to string-matching.

Granted, that sounds horrible!

But it’s the only way we can build a dependency-free6 .NET assembly while still making use of the already existing Fileserver.Client DLL.

Recipe for Disaster

With all that out of the way, how does the full exploit chain look like?

- Trigger deserialization vulnerability.

- Load

Fileserver.Client DLLfrom theGAC. - Send commands to the

FSin order to plant our malicious files next to the binary itself. - Create a new connection to the

FS, which forks the process, loads ourDLLsand executes our batch script. - 🎉🥳🎉

Here’s the final exploit for reference:

| |

Doesn’t look too fancy, now does it? Just about 100 lines of imperative, reflection-heavy code.

Demo

Some of the most anticlimactic things to watch are demos of actually launching an exploit:

| |

Why even bother, right?

Well, here’s my take on the situation:

No, I did not spend several hours making that video on an original Windows XP SP2 system. Even if I did: You can’t tell me how to live my life!

Conclusion

I’m so happy. I truly am.

After a lot of work, finally some security work to be extra proud of!

The presented vulnerabilities in isolation are pretty standard fare. Deserialization issues, an all-mighty service without authentication, susceptibility to DLL Hijacking, wrong assumptions.

But it’s the sum that makes them greater. That’s exactly the current state of exploitation as a whole: You’d be hard pressed to find single vulnerabilities that lead to a desired outcome. Most of the time, chaining them is the only way to do something meaningful.

Another thing of note: Even though binary exploitation is the ever beckoning final tier in information security, we didn’t need any of it. Pure logic bugs allowed us to do everything we could’ve hoped for.

And because we restricted ourselves to the vendor’s ecosystem, it didn’t even matter how the hosting system was patched and configured. Furthermore, we only used the system as intended7, so I imagine it’ll be rather difficult to detect the attack. That’s a really scary prospect, in my opinion!

As always: If you have any questions, suggestions or simply the desire to get in touch, feel free to holla at me.

Thank you so much for reading!

Acknowledgments

- Alvaro Muñoz for the aforementioned talk and the ysoserial.net tool.

- Markus Wulftange for his research on Bypassing .NET Serialization Binders, a recent addition to

.NETserialization vulnerabilities. - OnlyAfro for making the legendary HE’S BACK video. Matching their editing skills is a life-long endeavor.

- Excision & Downlink for their track “Existence VIP”, which is the perfect fit for hardcore exploitation demos.

- The person who archived a

Windows XP SP2VM image :^).

It gets a bit murky if new functionality is created by jumping into the middle of an instruction, though. ↩︎

Which is exactly why I’ve put two challenges inspired by it straight into a

CTF: Here and here. ↩︎The PHP

expectmodule has to be loaded. ↩︎In contrast to

ROPGadgets, these are actually bigger than a couple of bytes. ↩︎I’m explicitly not dunking on the developers! Stuff simply accumulates over time. ↩︎

We have a ton of dependencies, but only to the Base Class Library. ↩︎

Making a HTTP request (granted: it throws an exception), manipulating files like the legitimate program does. ↩︎