It's Not Mine: CVE-2025-64113

Welcome to “It’s not mine!”, a series of articles where I go over vulnerabilities found by other people.

Recently the media server Emby was on my mind again because an old vulnerability I’ve reported more than two years ago finally got assigned a CVE (CVE-2025-64325).

In the meantime, a much more interesting API vulnerability was disclosed (CVE-2025-64113):

This vulnerability affects all Emby Server versions - beta and stable up to the specified versions.

It allows an attacker to gain full administrative access to an Emby Server (for Emby Server administration, not at the OS level,).

Other than network access, no specific preconditions need to be fulfilled for a server to be vulnerable.

- GHSA-95fv-5gfj-2r84 advisory

Sounds interesting, right?

Actually, the issues turned out to be quite boring. But analyzing them touches on a few important concepts like entropy and randomness and techniques like patch diffing. Plus I needed a low-effort 2025 post badly and it’s 2026 already!

Password Reset Process

The advisory linked above mentions a passwordreset.txt file, so we already have a good idea what component is affected.

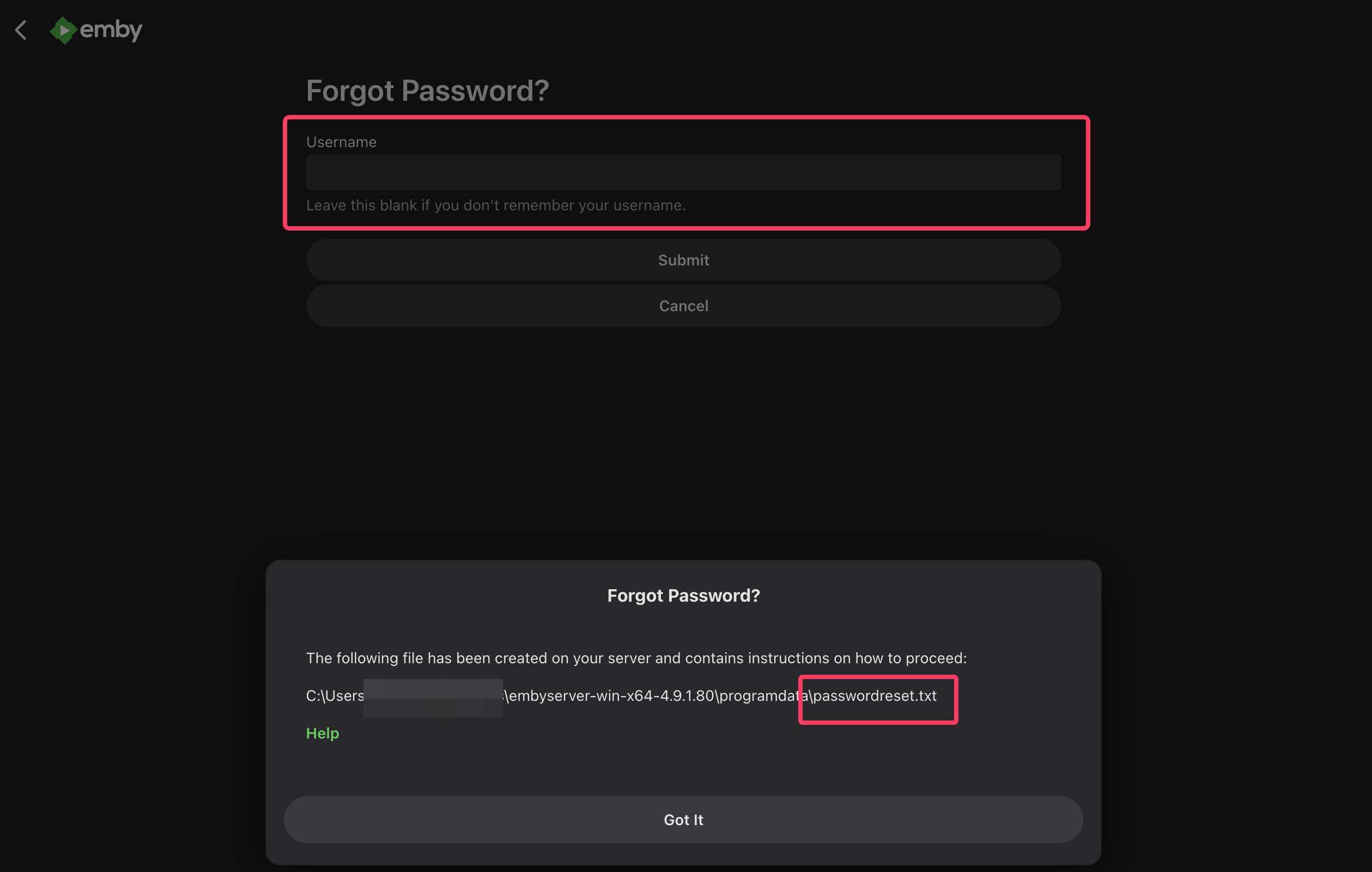

After creating a local (vulnerable) test instance, we can submit a “forgot password” form:

Figure 1: Submitting a forgot password form

Notice that the Username field can be empty. Let’s check the contents of passwordreset.txt:

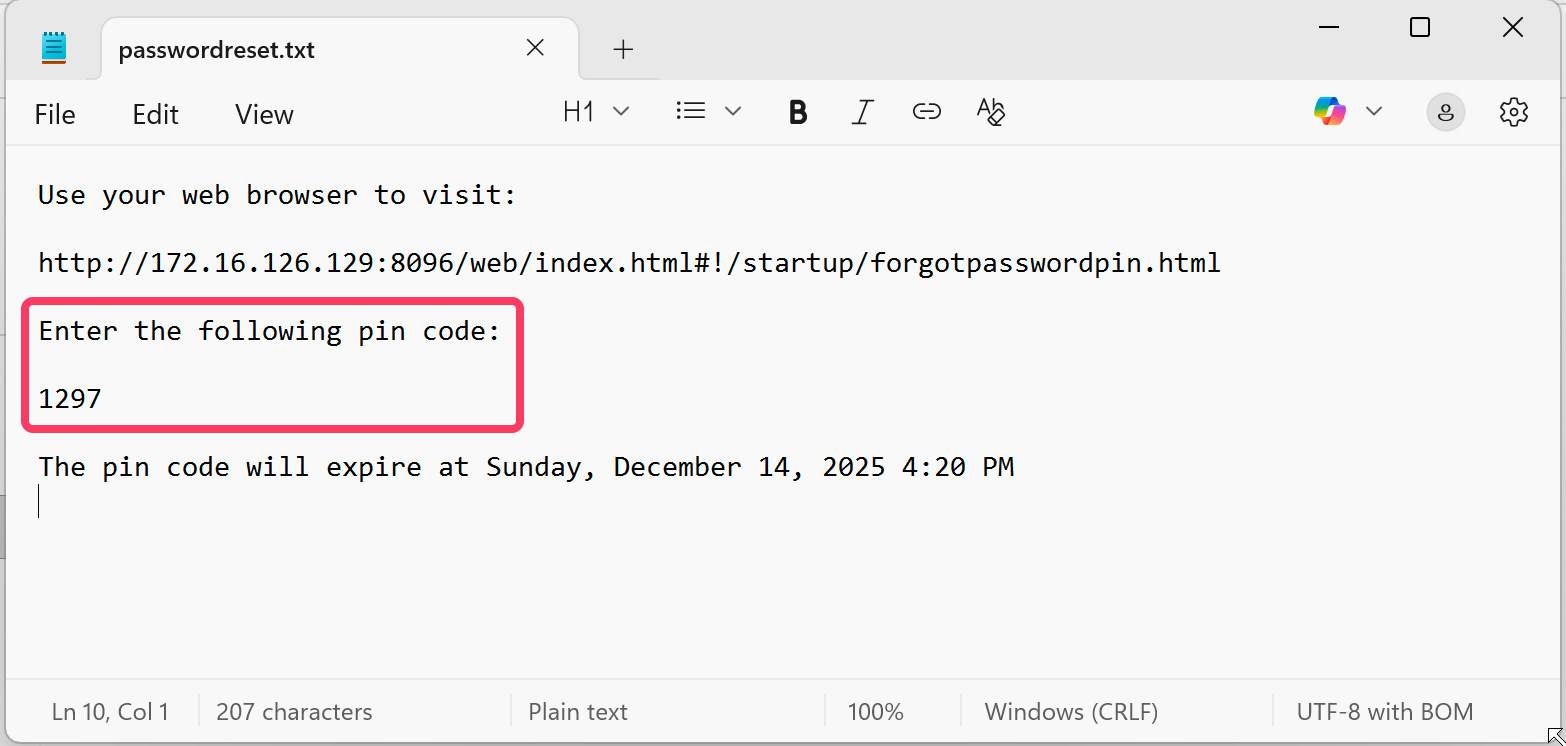

Figure 2: passwordreset.txt contains PIN and expiration date

Because user accounts are not tied to mail addresses, Emby writes a PIN to a local file only an administrator should have access to. That PIN needs to be entered on the specified page in order to trigger the password reset for the specified user. Or for all users if no username was provided.

A four digit PIN seems like it could be easily brute-forced without additional security measures in place. Before we jump to conclusions, though, let’s get more context by looking at the actual code.

Emby is not open source, but it’s written in C# and can therefore be decompiled with ILSpy or similar tools.

Patch Diffing Setup

In order to get a better understanding of the vulnerability, we want to see the difference between the last vulnerable and the fixed versions. Creating a diff of the two should provide us with anything we need to exploit the issue.

We start by downloading the last vulnerable and the fixed versions.

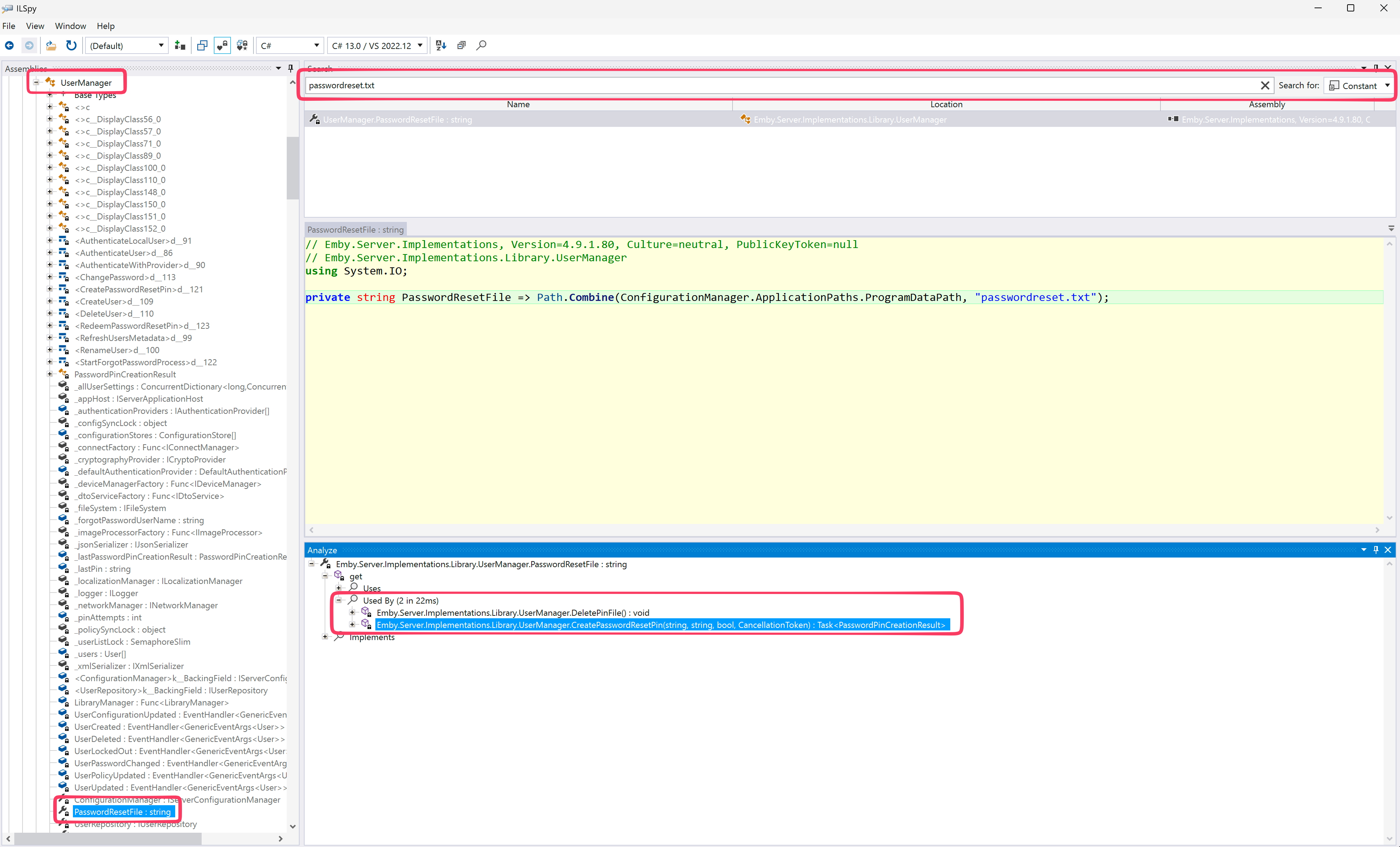

Ideally, we don’t need to decompile the whole project if we’re able to pin-point the vulnerable component first.

A good way to quickly identify the component(s) we are interested in is to search for strings that are probably used within said component. Those could be error messages or constants like file names:

Figure 3: Searching for “passwordreset.txt” constant in ILSpy

Searching for the “passwordreset.txt” string leads us to the UserManager, formally known as Emby.Server.Implementations.Library.UserManager. 🤵

Method names like StartForgotPasswordProcess and RedeemPasswordResetPin tell us that we’re on the right track.

Because the scope is so limited, we’re setting up the diff between vulnerable and fixed versions manually. We’ll talk about a better approach for bigger projects later.

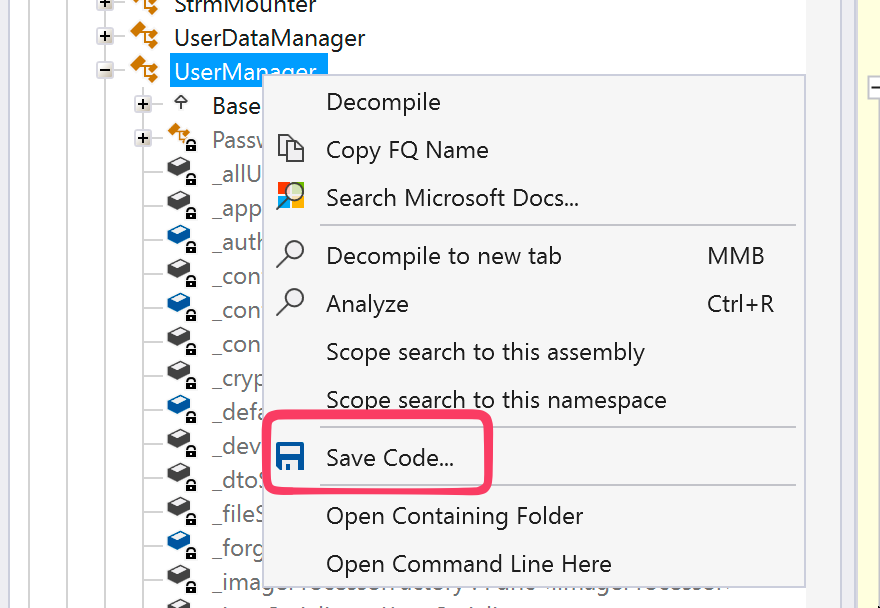

From within ILSpy, we can simply save the decompiled code for both versions:

Figure 4: Manually saving the decompiled code with ILSpy

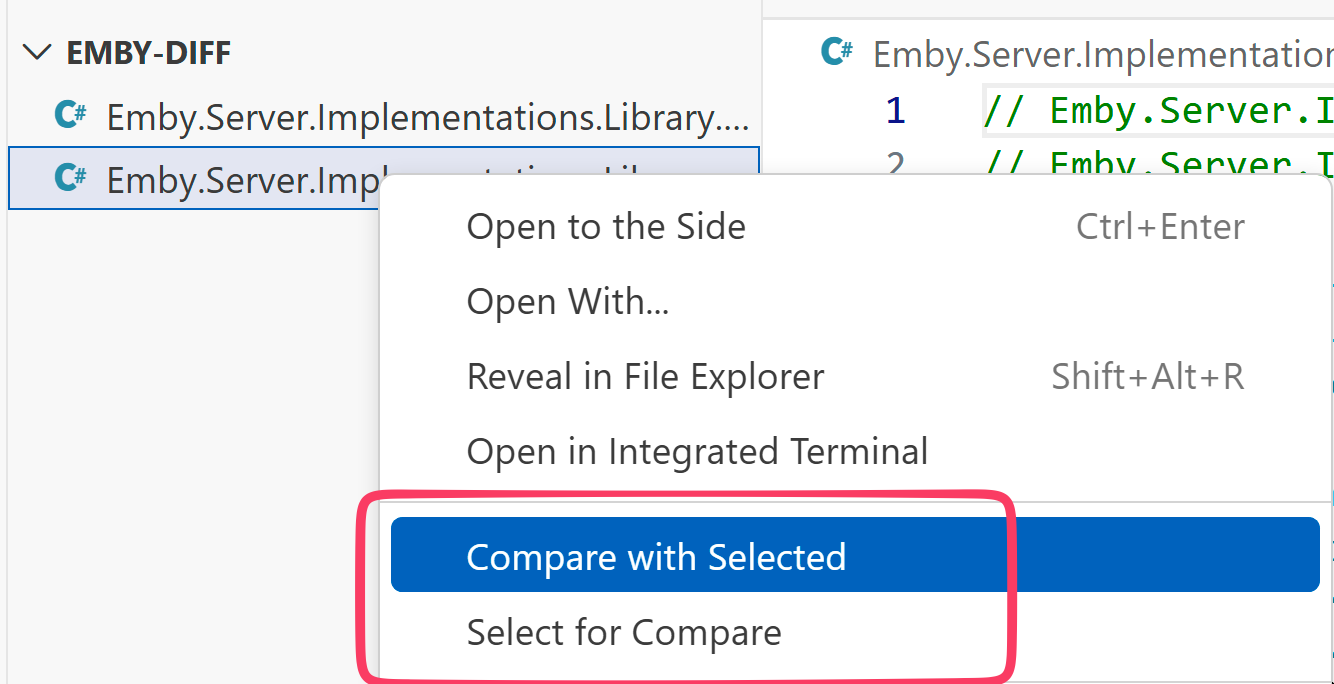

Now we open the directory containing both files in VSCode. After right-clicking the vulnerable version and selecting the “Select for Compare” option, we right-click the fixed version and select the “Compare with Selected” option:

Figure 5: Comparing both files in VSCode

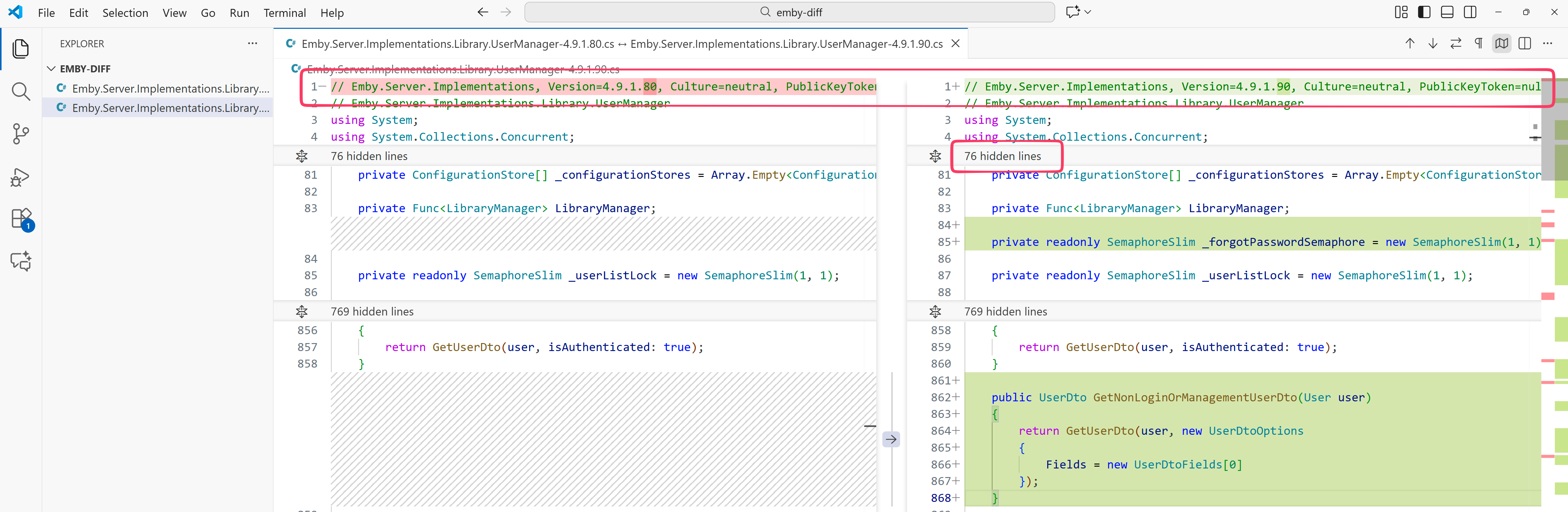

Voilà! We get a clean diff inside a nice GUI that lets us expand and collapse portions of the code we’re not interested in:

Figure 6: Diff view of VSCode

Beautiful.

For bigger projects, the ILSpyCmd tool can be used for bulk-decompilation.

I like to create a Git repository where every commit corresponds to a specific version of the software. This way, we get access to Git’s own diff command and can use the Git integration of editors like VSCode for more visual flavor.

Markus Wulftange also uses this approach and wrote about it in his analysis of CVE-2025-59287.

Difftheria

Now that we have a diff, let’s go over the changes. We won’t go over every single change, instead covering them in broad strokes.

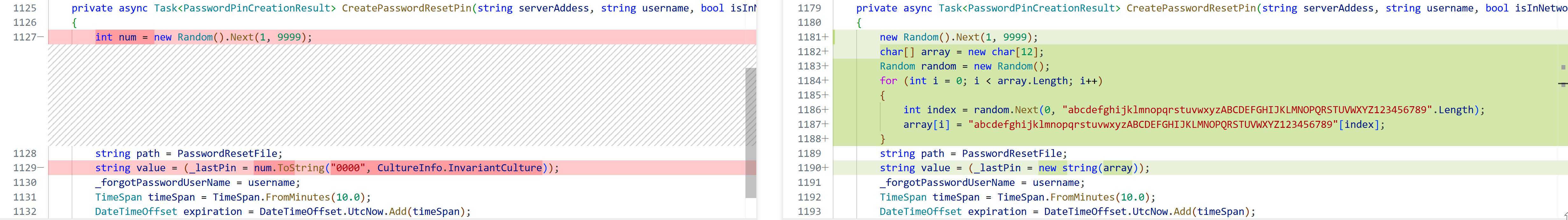

The first big one concerns the PIN format. Whereas before it consisted of four digits, it is now made up of 12 alphanumeric characters:

Figure 7: Diff of CreatePasswordResetPin method

Combined with a newly introduced semaphore, this immediately looks like a brute-force vulnerability.

private readonly SemaphoreSlim _forgotPasswordSemaphore = new SemaphoreSlim(1, 1);

Think of a semaphore as a bouncer in a nightclub. A bouncer only lets a specific amount of people inside a club at any time. A semaphore only let’s a specific number of threads execute a piece of code at any time.

In essence, this semaphore is used as a mechanism for throttling requests, as can be seen in the StartForgotPasswordProcess method:

| |

By using the non-blocking Task.Delay, the execution is delayed by three seconds while the thread can do other work.

This is it? A simple brute-force issue? Let’s check for any throttling-related code in other parts of the code base. If none is present, the introduced change is probably at the heart of the vulnerability.

A good place to start is the ForgotPassword endpoint itself.

Emby uses “ServiceStack”, which is an alternative framework to the popular “ASP.NET Core”. ServiceStack doesn’t make use of traditional controllers, instead two distinct pieces are needed.

First, a DTO (Data Transfer Object) with annotations that set the path of the endpoint among other things:

| |

The other piece is a service that contains the actual code that gets triggered when the ForgotPassword endpoint is called with the correct arguments (only the relevant method is shown):

| |

In here, our familiar UserManager.StartForgotPasswordProcess method gets called. So no rate-limiting or throttling on the individual controller/service level.

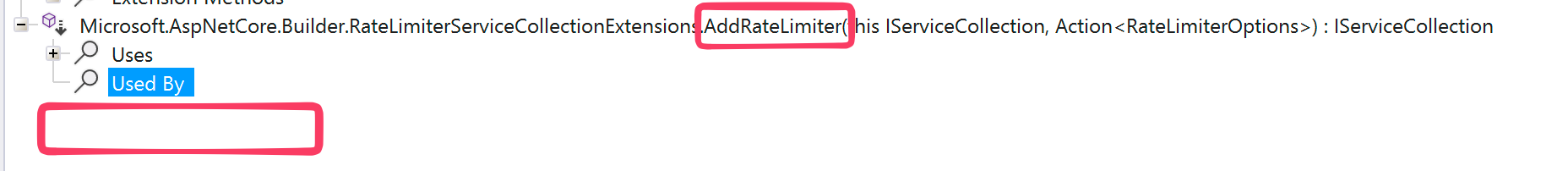

What about some global rate limiting mechanism? ServiceStack has a dedicated documentation page about it.

Essentially, they rely on the Microsoft.AspNetCore.RateLimiting package themselves.

Searching for the AddRateLimiter method mentioned in the documentation and analyzing the references to it, we find zip:

Figure 8: AddRateLimiter is not used anywhere

I think it’s safe to assume that no global rate-limiting or throttling is in place, which verifies our theory of the vulnerability being a boring brute-force issue.

Finally, let’s have a closer look at the method that actually checks the validity of the PIN. The only difference between the vulnerable and fixed versions is the usage of the semaphore. Here is the version we’re trying to attack:

| |

As we can see, the passwordreset.txt file gets deleted (DeletePinFile) the first time the method is called. The actual comparison happens with an in-memory PIN (_lastPin). That PIN gets deleted once we hit three wrong attempts.

This enables the following exploitation steps:

- Trigger password reset for all users

- Attempt to guess the correct pin three times

- Repeat the previous two steps

- …

As we saw in the image above, the PIN in the vulnerable version gets generated like this:

int num = new Random().Next(1, 9999);

Because the upper bound is exclusive, the range of possible values is 0001 to 9998.

As we’ll see next, it’s quite trivial to brute-force the correct PIN, even with the three attempt constraint in place.

Exploitation

Now it’s time to exploit the issue in the dumbest way possible. Because why get unnecessarily fancy?

| |

That should take forever, right? Here are a couple of attempts:

[+] SUCCESS with pin 9095. Password reset for the following users: ['admin']

[+] It took 38.65023374557495 seconds and 7770 requests

[+] SUCCESS with pin 4565. Password reset for the following users: ['admin']

[+] It took 9.948091983795166 seconds and 2006 requests

[+] SUCCESS with pin 4726. Password reset for the following users: ['admin']

[+] It took 13.857664108276367 seconds and 2778 requests

We should play the lottery:

[+] SUCCESS with pin 793. Password reset for the following users: ['admin']

[+] It took 2.6026036739349365 seconds and 554 requests

Or not:

[+] SUCCESS with pin 4746. Password reset for the following users: ['admin']

[+] It took 427.4628806114197 seconds and 68227 requests

Wow, we’re not even going to bother with optimizing this. After all, it’s a low-effort post!

Random Elephant in the Room

What if it were a high-effort post, though? How could we improve the exploit? Maybe sending more requests in bulk so that we can smuggle in more attempts before the in-memory pin gets deleted? Sure, but let’s take a step back and look at the response of the server when requesting a password reset:

{

"Action":"PinCode",

"PinFile":"C:\\Users\\blurred\\Downloads\\embyserver-win-x64-4.9.1.80\\programdata\\passwordreset.txt",

"PinExpirationDate":"2025-12-14T18:10:52.0174231Z"

}

What do we see except for the disclosure of a file system path? A pretty accurate timestamp. Shockingly accurate, actually.

The PinExpirationDate is exactly 10 minutes after the initial timestamp:

TimeSpan timeSpan = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(10.0);

DateTimeOffset expiration = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow.Add(timeSpan);

An attacker could subtract the ten minute expiration time and would get the exact timestamp at which new Random() was called.

Why is that important? Well, we have to read the documentation for the parameterless Random constructor:

[…] If it is run on .NET Framework, because the first two Random objects are created in close succession, they are instantiated using identical seed values based on the system clock and, therefore, they produce an identical sequence of random numbers.

Before we get too excited, let’s do a quick test to see if “system clock” refers to the actual time:

| |

And the result when running under .NET Framework 4.7.2:

[*] Generated PIN: 1866

[*] Formatted expiration date to be send to the client: 2026-01-13T18:35:18.8705742Z

[*] Time-based PIN is 6645

[*] Tick-based PIN is 1866

As we can see, not the actual time is used for seeding Random, but a value we can obtain via Environment.TickCount:

A 32-bit signed integer containing the amount of time in milliseconds that has passed since the last time the computer was started.

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/api/system.environment.tickcount?view=netframework-4.7.2

Additionally, Emby uses .NET (Core), which doesn’t use the system clock as a seed:

In .NET Core, the default seed value is produced by the thread-static, pseudo-random number generator, so the previously described limitation does not apply. Different Random objects created in close succession produce different sets of random numbers in .NET Core.

A dead-end for exploitation, but good to know nevertheless.

Summary

When combined, these three issues make the account takeover process trivial:

- attacker doesn’t need to know an account name

- no rate-limiting and/or throttling

- low entropy of PIN

So while it’s a rather anti-climactic vulnerability, there are a few lessons here.

Use high-enough entropy for secrets like PINs or magic links. Put rate-limiting in place (possibly in combination with throttling). And while not exploitable in this case, be generally mindful about how randomness is generated.

The same techniques we used for analyzing can be used for bigger patches and more interesting vulnerabilities.

During the process of writing this post, I’ve discovered that another person with the handle Cane has already published a post about the vulnerability (see Resources). It’s not clear if that person discovered the issue, because the Emby advisory page on GitHub lists another name in the credits section.

But one thing is clear: It’s not mine!

Resources

CVE-2025-64113 Advisory

https://github.com/EmbySupport/Emby.Security/security/advisories/GHSA-95fv-5gfj-2r84

Last vulnerable release

https://github.com/MediaBrowser/Emby.Releases/releases/tag/4.9.1.80

Fixed release

https://github.com/MediaBrowser/Emby.Releases/releases/tag/4.9.1.90

Blog post by Cane (Chinese) https://hicane.com/archives/geek-embyserver-gao-wei-an-quan-lou-dong

Emby forum thread that mentions the issue

https://emby.media/community/index.php?/topic/143784-possible-remote-access-exploit-deleting-media-on-emby-servers/

Emby docs for password reset (not updated at the time of writing)

https://emby.media/support/articles/Admin-Password-Reset.html

Semaphore bouncer analogy borrowed from Patrik Svensson :)

https://stackoverflow.com/a/40473